17 minutes reading time

Commentary from the Betashares portfolio management desk by Head of Fixed Income Chamath De Silva, providing an overview on fixed income markets:

- The policy shock from the reciprocal tariff announcement triggers global repricing of risk premiums across asset classes.

- New geopolitical framework and desire from the US administration to undertake profound structural reforms creates massive risks over both the short and long term.

- Australian fixed rate bonds remain attractive, with US-Treasury induced volatility driven primarily by technical rather than fundamental factors.

Volatility returns to markets

Far from defusing near-term risks, the unveiling of reciprocal tariffs has heightened policy uncertainty and driven risk premiums across asset classes markedly higher. In the two days since the “Liberation Day” announcement, US equities were down around 10%, high-yield credit spreads widened by approximately 100 basis points, and 10-year Treasury yields fell by 20 basis points, with larger initial moves at the front end as a US recession increasingly becomes the base case. However, global fixed income markets remain in flux and a surge in interest rate volatility has coincided with an aggressive bear steepening of the US Treasury curve in recent sessions (long-term yields rising by short-term yields), alongside a continued widening in spreads.

This is a much longer than usual WHIB and I feel what’s happening is quite profound for both markets and the global economy. That said, I don’t want to bury my conclusions in the body. In summary, I believe that key members of the administration have an overarching aim for markets to push long-term Treasury yields lower, while also narrowing both the trade and budget deficits. Essentially, this is to facilitate their long-term objective to rebalance the US economy away from fiscal accommodation to private sector investment and increase the manufacturing share at the expense of services. They haven’t been subtle about it. The real surprise is just how much pain in equities and the real economy they seem willing to tolerate to achieve it. Feel free to skip ahead to the later sections, where I go into bond and credit markets in more details, but I wanted to share my thoughts on this new macro and geopolitical regime first.

The “formula” and the bigger picture

A good place to start is the actual “formula” for how the reciprocal tariffs were determined. While the administration had previously suggested they would be based on formal trade barriers, currency manipulation, and non-trade consumption taxes (like the GST in Australia or the VAT in Europe), the actual rates were calculated using a laughably simple approach: each country’s goods trade deficit with the US, expressed as a share of its total exports to the US, with this share divided by two, because the administration was feeling “charitable”.

There are a few things this tells us. First, bilateral trade deficits are treated as inherently bad. This suggests that at least some in the administration view global trade as a zero-sum game. Second, services appear to have been excluded entirely. That decision disproportionately penalises countries that export goods to the US but may be net importers of US services and suggests an ideological view that prioritises manufacturing jobs over services jobs.

That kind of rebalancing, however, doesn’t happen overnight. It requires significant capital investment, typically over years. And it’s made even harder by the sheer lack of clarity around future trade policy. There’s a risk that businesses delay investment until they know the rules of the game. On that note, it’s worth touching on the intellectual framework being constructed around these policies. A lot of it can be traced back to figures like Council of Economic Advisers Chair Stephen Miran and Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who have been shaping what appears to be a serious, if questionable, effort to rethink both trade and fiscal policy from the ground up.

Now if we assume that the sole purpose of the tariffs isn’t simply to raise tax revenues to pay for the tax cut extension, it’s worth diving into some of the theoretical rationale from members of the administration. Much of the thinking behind the new trade framework stems from a paper Miran wrote before joining this administration, effectively a how-to guide for re-engineering the global trading system (which he has since followed up with a piece this week under the Whitehouse’s masthead that covers very similar ground). The paper proposes replacing today’s efficiency-driven globalisation model with a “values-aligned” one. In practice, that means forming a bloc of like-minded nations who enjoy preferential trade access, while imposing tariffs on non-cooperative states, key tenets of the so-called “Mar-a-Lago accord”.

The plan aims to weaken the US dollar to enhance manufacturing competitiveness. Controversially, it proposes asking foreign creditors to swap their short-term Treasuries for new long-term, low-yield bonds, or face taxes on their reserves. Access to US consumers and security would come with new conditions. The aim seems to be to rebalance global trade, refocus the US economy around private-sector investment and away from fiscal accommodation, and still retain the reserve status of the dollar. It’s an ambitious attempt to thread the needle, but it carries massive risks.

The risks of reversing global trading patterns

The Mar-a-Lago Accord may sound coherent in theory, but the mechanics are risky. The proposal to force foreign official holders to swap short-dated Treasuries for ultra-long, low-yield bonds risks being seen as a soft default. Mark-to-market losses would be material, and it’s unclear whether continued access to the US consumer or vague security guarantees would be enough to take such a haircut.

At the same time, some in the administration may be ignoring the evolving nature of Treasury demand. Central bank holdings have been declining in recent years, with a growing share now in the hands of domestic asset managers, hedge funds, commercial banks, and of course, the Fed. In contrast, foreign holdings of US financial assets have increasingly moved towards equities, including large unhedged holdings from not only traditional “real money” like European and Japanese pension funds, but also sovereign wealth funds and even central banks, with the Swiss National Bank’s equity portfolio the most well-known. It’s easy to forget that the US trade deficit has been funded by a capital surplus from foreign inflows. Moves to reverse global trade will also likely reverse foreign inflows into US capital markets.

More fundamentally, the S&P 500 has thrived under a global structure where the US imports low-margin goods and exports high-margin services, especially digital ones. In addition, US equities have outperformed, helped by economic outperformance of the US, which has largely been a function of outsized fiscal accommodation. This has underpinned exceptional corporate profitability. If that model is being actively unwound, the market likely isn’t prepared for the compression in both earnings growth and the multiple that might follow.

Lower yields at any cost?

Let’s turn to the budget side. Secretary Bessent has been explicit in stating that his goal is to get the 10-year Treasury yield lower. This likely serves three purposes:

- Reducing the Federal government’s borrowing costs, especially given that interest payments made up around 49% of the budget deficit in FY2024. However, yields will need to be taking much lower and held there for some time, given the weighted average maturity of existing Treasuries outstanding is around just under 8 years.

- Lowering mortgage rates, which are referenced off the 10-year yield would deliver a clear political win.

- Reducing the cost of capital to help finance a domestic re-industrialisation push.

Part of the reason we’ve remained constructive on bonds is that it’s clear the administration would prefer lower yields over supporting equity prices. There’s also a broader ideological pivot underway: away from government-led demand and back towards private sector investment, no doubt influenced by Argentina’s Milei government and its recent attempts at structural reform. Austerity will put downward pressure on aggregate demand, increasing the risk of a downturn. And while a recession would likely lower 10-year yields, it would also widen the deficit due to collapsing tax revenues. I’ve previously written about the dangers of DOGE, and it’s worth remembering that recessions can quickly become non-linear, especially when paired with ongoing fiscal tightening.

What this all means for the Fed?

We’re now in a world where fiscal and trade policy matter more for markets than monetary policy. This is a shift, but the Fed still matters a lot. Ultimately, it will be the FOMC that determines whether the administration succeeds in its aim of pushing long-term yields lower. The challenge for the Fed is the hard data is still holding up somewhat well. Both Core PCE and headline CPI remain above target on a year-on-year basis, and unemployment is still low. However, forward-looking indicators are painting a much darker picture.

The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model is pointing to an outright contraction, this may reflect technical factors, such as a spike in imports, but indicators of labour market health are also weakening. Although the headline March payrolls print beat estimates, the underlying details were less encouraging. Alongside negative revisions to previous months, wages growth was soft, and there was a second consecutive monthly decline in the share of prime-age workers (25-54) in the population. Separately, the Challenger Job Cuts survey reported a sharp increase in layoffs in March, while the employment component of the ISM services data pointed to a contraction in hiring intentions.

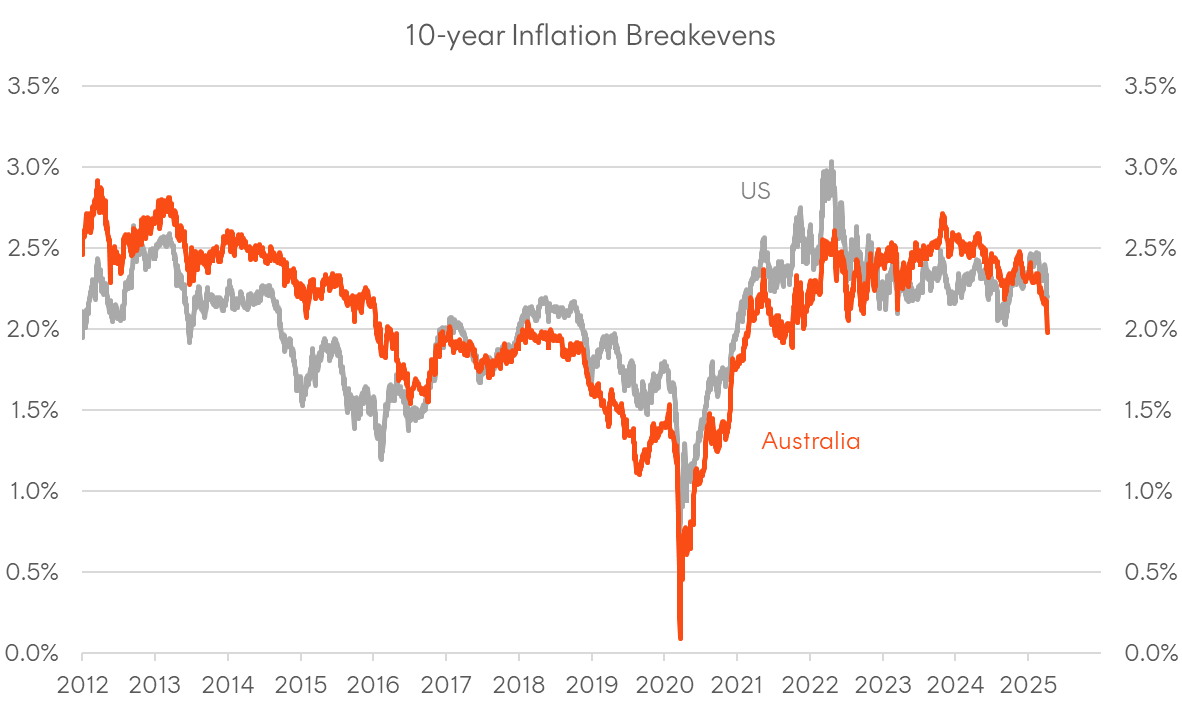

In addition to the widening gap between soft and hard data, there is an outright divergence in the various measures of inflation expectations. Survey-based measures point to inflation fears persisting, with the University of Michigan’s 5-10-year expectation recently rising to a multi-decade high of 4.1% (p.a.), while market-based expectations have collapsed. Since the reciprocal tariff announcement, 10-year breakevens have plunged around 30 basis points and 5y5y forward breakevens dropped below 2% for the first time in years.

As it stands, economists and commentators are still divided over the inflationary impacts of a fresh trade war, but my own view, and taking cues from market signals, is that it’ll likely be far more impactful for growth than inflation over the longer-term. This echoes the experience of the prior trade war during Trump’s first term. Back in 2018, the Fed and much of the consensus overestimated the inflationary impulse and underestimated the impact on growth and the Fed’s policy error forced them into a dovish pivot heading into 2019. I’d also argue that it wasn’t the 20% fall in equities that triggered the pivot, but the freezing of credit markets. High yield and loan issuance came to a standstill, and it’ll take something similar for the Fed to bring forward rate cuts in the absence of the hard inflation or employment data cooling.

On the recent US Treasury volatility…

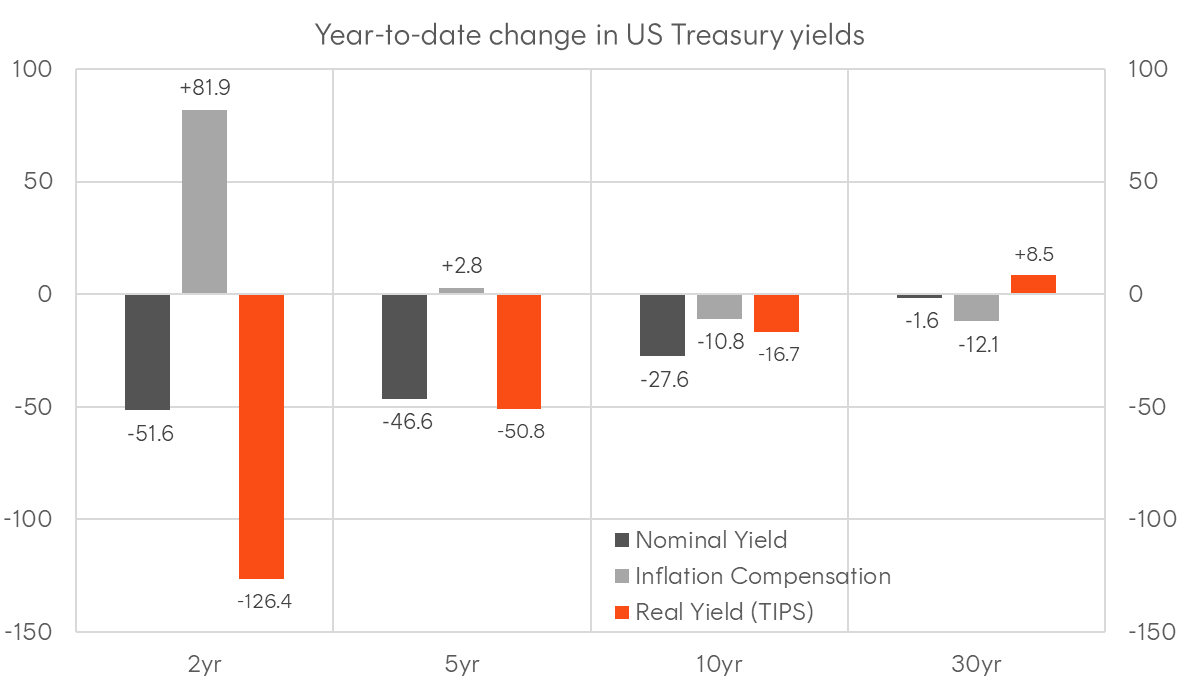

Despite a significantly higher recession risk for the US economy, the past couple of sessions have seen a disorderly bear steepening in the US Treasury curve, with long-term yields now trading above pre-tariff levels. What is particularly notable is that this has occurred amid a broader risk-off backdrop, with other recession signals such as a weaker USD/JPY and falling crude prices pointing in the opposite direction. This suggests the move is largely technical and driven by positioning. Further supporting this view, the bear steepening in nominals has come alongside a surge in real yields, with 30-year real rates now back around their cycle highs. This reinforces the tightening in financial conditions, even as macro fundamentals continue to deteriorate.

As mentioned earlier, the ownership composition of US Treasuries has shifted away from foreign official institutions towards domestic players, particularly hedge funds. Many of these have built up sizeable “basis trade” positions, running relative value books that are long cash Treasuries and hedged with liquid synthetic duration instruments such as futures or swaps. These positions have been attractive due to deeply negative swap spreads, allowing investors to clip generous carry.

However, with the recent surge in interest rate volatility, we are likely seeing a wave of position liquidation. Key event risks for the dealer community, such as CPI releases and Treasury auctions, are forcing highly leveraged players to shed duration risk and liquidate physical Treasuries and unwind basis trades, with the USD 30-year swap spread plunging to an all-time low of -97 basis points at the time of writing (i.e. 30-year Treasury yields are almost 100bps higher than equivalent risk-free swap overnight indexed swap rates).

All told, this appears to be a technically driven move, not one anchored in improving macro fundamentals or inflation fears. However, it does impose a de facto tightening in financial conditions, one not driven by the data, but which arguably worsens the macro-outlook and strengthens the case for rate cuts.

What this all means for Australian bonds?

Australia, being hit with only a 10% tariff, might be seen as getting off relatively lightly. However, as one of the few countries running a goods surplus with the US, we could argue we have been somewhat hard done by. Either way, with no retaliatory tariffs and a fresh trade war between the US and other major economies now unfolding, the domestic inflation picture remains far more benign, and the primary downside risk is clearly to growth. The main impact of this latest round of tariffs is not necessarily the direct effect of increased barriers to bilateral trade, but rather the indirect consequences of a slowing global economy, including potential weakness in commodity prices and broader risk sentiment.

We have been constructive on Australian fixed-rate bonds for some time, based on a combination of real yields reaching fresh cycle highs, highly attractive term premia on Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS) – even relative to US Treasuries – and inflation expectations that are clearly trending lower. The 10-year breakeven is now just 2 per cent. In addition, technical liquidity developments have added further value to Australian government bonds. Swap spreads recently turned negative (with swap rates falling below 10-year government bond yields), hitting a fresh all-time low, though they are now finally showing signs of widening amid the dealer community getting over-extended on the swap spread, which is now seeing an unwind.

Perhaps more importantly for rate cut prospects, hard inflation data had already been moderating ahead of expectations. It is also likely that further disinflationary pressures will emerge as global growth deteriorates—a risk the RBA alluded to in its April statement. Against this backdrop, the additional rate cuts now being priced into the market appear reasonable. Structural growth remains weak, inflation is trending lower, and long-term inflation expectations are anchored at the bottom of the RBA’s target band. Despite last week’s bond rally, the 10-year yield remains above the cash rate, offering compelling value for most and representing a strong buy for those anticipating a global recession.

Moreover, the disorderly bear steepening in US Treasuries—driven by technical factors—is spilling over into the Australian market, leading to a simultaneous rise in yields and spreads. This imposes an exogenous tightening in domestic financial conditions, unrelated to Australia’s macroeconomic fundamentals, and in my view, further strengthens the case for the RBA to cut rates.

What’s happening in credit?

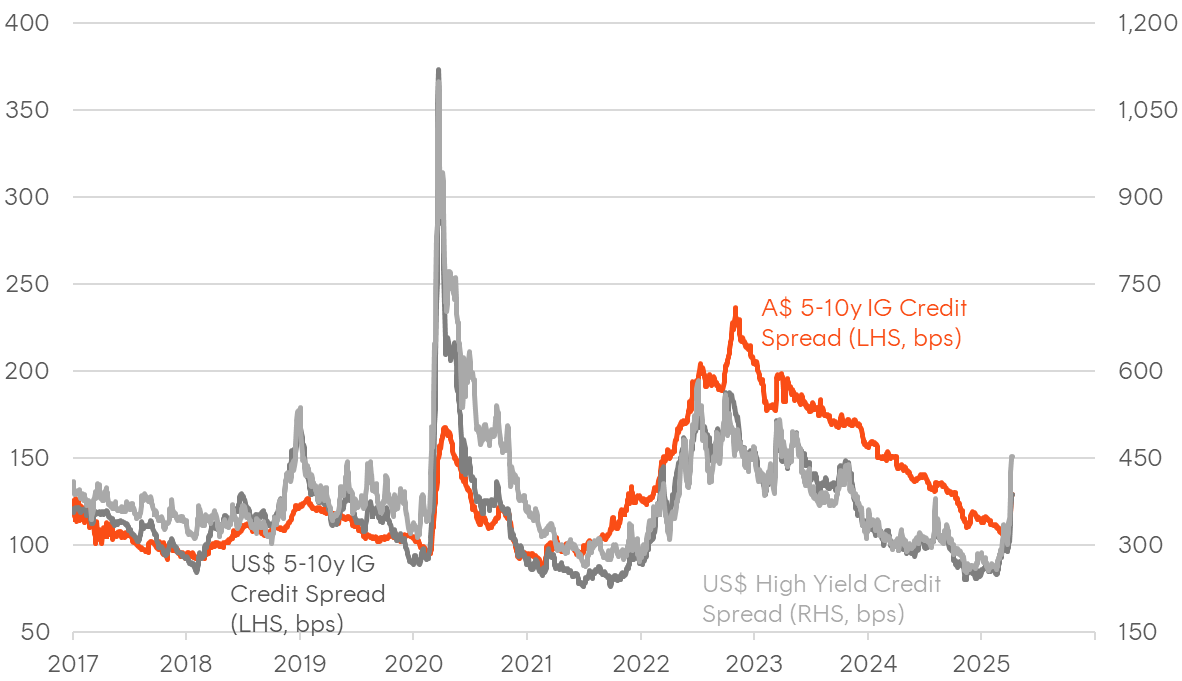

The key indication that the August 2024 deleveraging event (the “yen carry trade unwind”) was a markets and positioning story only, rather than a harbinger of recession, was the behaviour of credit markets. In contrast to equities and measures of equity volatility, where the VIX reached its highest intraday level since the pandemic, credit spreads were relatively well-behaved, widening only modestly, with AUD investment grade spreads barely widening at all.

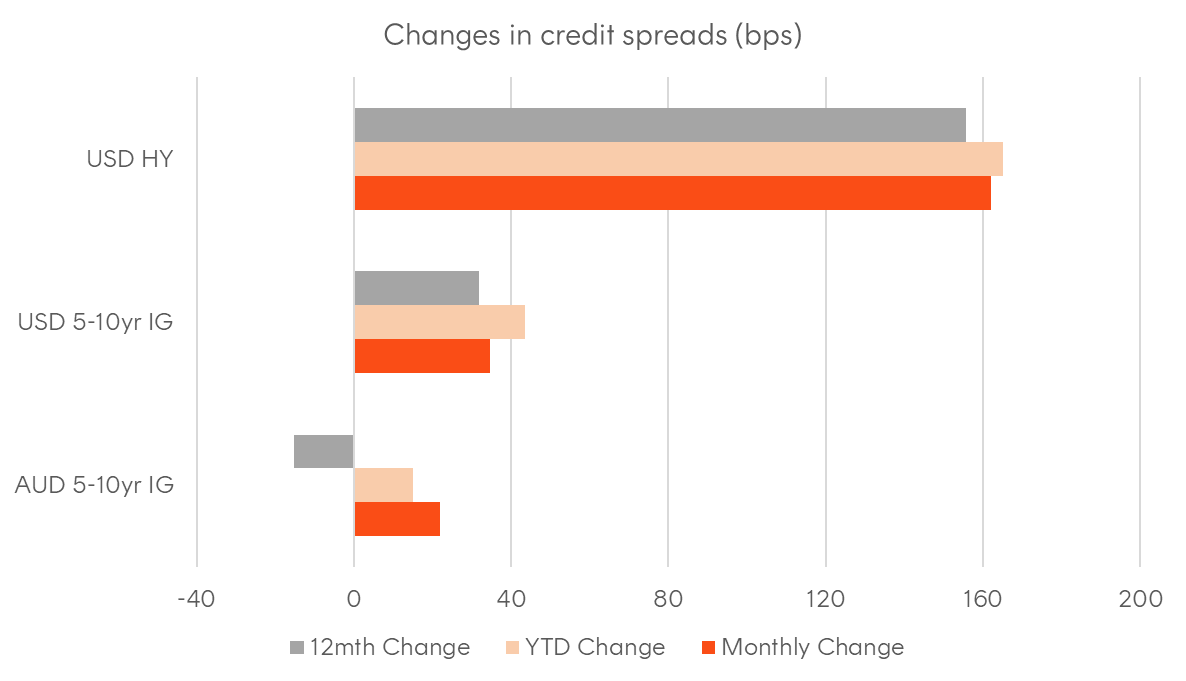

This episode feels different. Credit is now telling the story of a rapidly emerging growth scare. It is worth pointing out that, heading into the US Presidential inauguration, spreads across US dollar high yield were trading near their tightest levels in more than a decade. Some degree of widening shouldn’t have come as a surprise. However, the tariff shock has created conditions across the broader corporate credit complex that are uncomfortably reminiscent of the very early days of the pandemic. Not only are spreads experiencing double-digit daily moves, but they’re also happening in recent sessions alongside a rates selloff, with price discovery becoming more and more questionable across both local AUD and global credit markets.

At the time of writing, US high yield spreads are more than 160 basis points wider for the month, with significantly larger moves observed in the lower-quality segments. Emerging market sovereign spreads are also widening, particularly for nations disproportionately affected by the reciprocal tariffs. US investment grade spreads are around 40 basis points wider, and even if a global recession is avoided, it is likely that spread widening will persist, especially if this bout of policy-induced volatility continues.

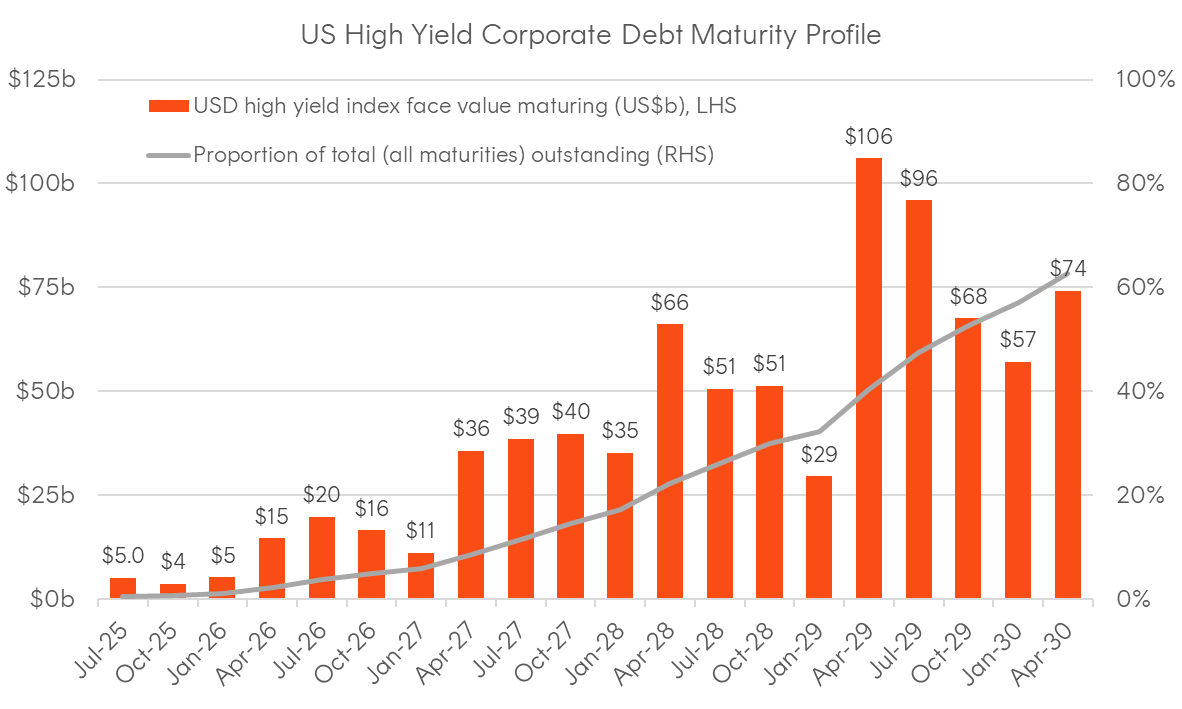

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of this latest phase of the trade war is the timing. You may recall that during the pandemic, following historically aggressive easing policies from global central banks and governments, many corporates were able to term out their USD debt at very low rates, with most maturities five years or longer. We are now likely around 12 months away from the first major refinancing cycle of the post-pandemic period, beginning with US high yield. This also coincides with broader measures of global liquidity tightening, as central banks seek to move away from pandemic-era policies and continue shrinking their balance sheets.

The level of credit spreads reflects several factors, the most obvious being default risk and liquidity risk. However, policy uncertainty and volatility in other asset classes, such as equities and interest rates, also play a significant role in determining equilibrium spreads. For investment grade credit, where traditional default risk is largely negligible, these macroeconomic and liquidity-related factors tend to dominate. A VIX averaging above 25 over the next 12 months would be consistent with US investment grade spreads also averaging at higher levels. In addition, the presence of a mercurial US administration increases the range of potential outcomes for the Federal Reserve, which raises interest rate volatility and, in turn, contributes to wider credit spreads. Combined with the upcoming refinancing cycle over the next few years, we are likely to see spreads average meaningfully wider than they have in the recent past.

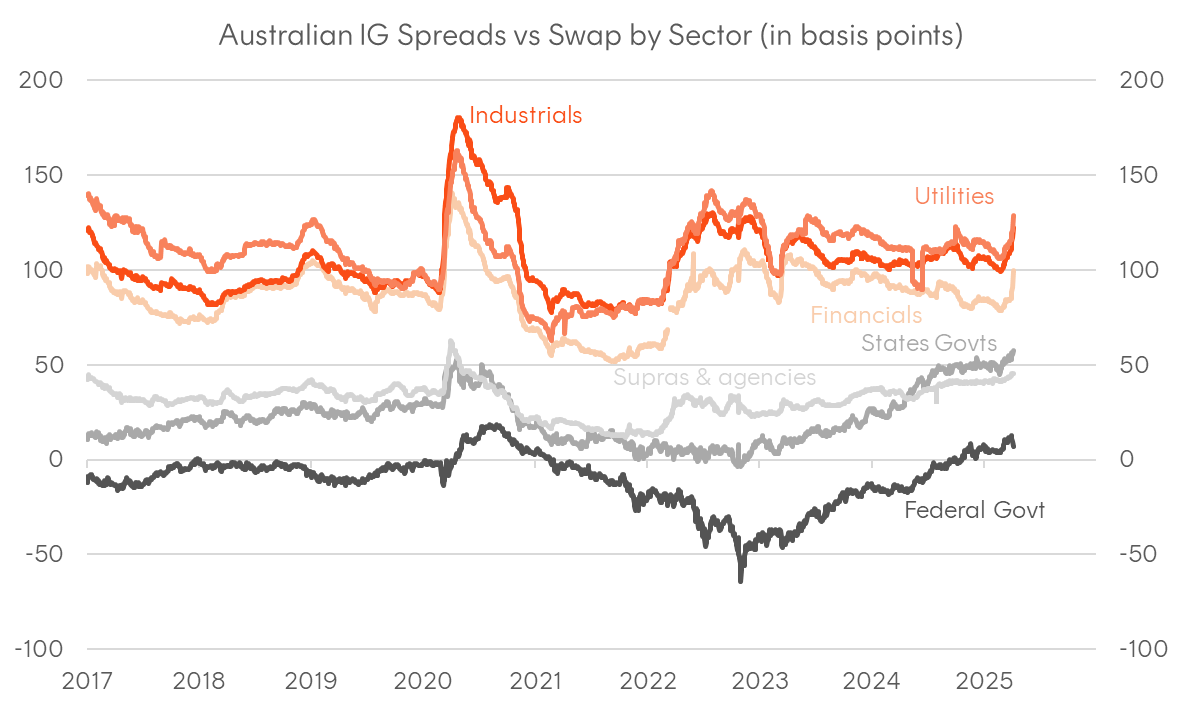

In the AUD credit market, global developments still matter. However, there tends to be much less leverage in our market, and as a result, spread widenings during major risk-off phases are typically more gradual and less extreme than in USD markets. As mentioned in my domestic bonds section, one notable development of late has been the move in AUD swap spreads into negative territory, making government bonds appear cheap relative to synthetic duration. AUD corporate and floating rate credit are typically priced to swap, meaning that wider swap spreads, which we’ve seen in recent days, increase the spread to government bonds, all else being equal. When corporate spreads also widen relative to swap, it creates a double impact, which we have seen play out in recent sessions. This dynamic arguably sets up corporate bonds for a period of underperformance against government bonds, at least in the short term.

Of course, spread widening can only go so far before the additional yield, or carry, becomes too attractive to ignore, and high-grade AUD credit is starting to look quite interesting, especially if you have a 2-year+ horizon, even if the spread widening can continue in the short term.

Chart 1: US Monthly trade balance

Source: US Census Bureau

Chart 2: YTD change in US Treasury yields

Source: Bloomberg as at 7 April 2025

Chart 3: Weighted average interest expense and weighted average yield on US Treasuries outstanding; excludes T-bills;

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 4: 10-year inflation breakeven

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 5: The US long-end selloff – 30-year nominal yields (top panel), real yields (middle panel) and swap spreads (lower panel)

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 6: Selected credit spreads to government (OAS)

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 7: Changes in selected credit spreads to government (OAS) in basis points

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 8: USD high yield maturity profile

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 9: Australian fixed income relative value; spreads to swap in basis points

Source: Bloomberg