The 7 principles of an investing plan

6 minutes reading time

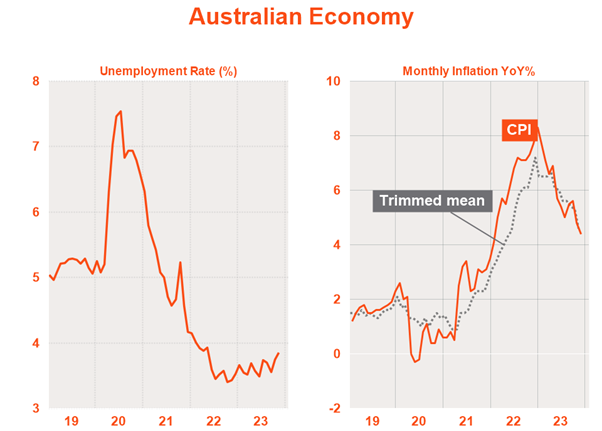

Having enjoyed a better than feared consumer-led recovery from COVID lockdowns, Australia’s economy in recent years has quickly been beset by a new problem: very high inflation, caused principally by stronger-than-expected demand running ahead of a slower-than-expected supply response.

Australia is not alone in facing this problem, with central banks around the world forced into aggressively raising interest rates from their COVID-low emergency levels to contain demand and pricing pressure – lest high inflation become embedded through an increase in inflation expectations and a self-reinforcing wage-price spiral.

The mantra of central banks has been to “not repeat the mistakes of the 1970s” where a series of oil price shocks led to a ratcheting up in inflation for over a decade. Interest rates in most countries, including Australia, have been lifted to above-average restrictive levels.

Yet while the hope was that inflation could be contained without the need for a global recession, history suggested otherwise. Getting inflation down from high levels has never been achieved in modern times without a recession. History also suggested that once economic growth slowed to a sufficient degree, a ‘tipping point’ can be reached whereby a hard landing is hard to avoid.

An economic ‘soft landing’: the runway is in sight

As we head into 2024, however, the news is so encouraging it’s almost hard to believe.

Although Australian and global economic growth has slowed, it has proven more resilient than expected – unemployment rates globally are still low, and recession has been avoided.

At the same time, the resilience in economic activity has not come at the expense of inflation remaining stubbornly high. Inflation has been falling broadly in line with expectations. Inflation is still too high, but it’s moving in the right direction. So much so that central banks have slowed the pace of interest rate increases and are starting to contemplate lowering interest rates at some stage this year.

Source: LSEG Datastream, Betashares.

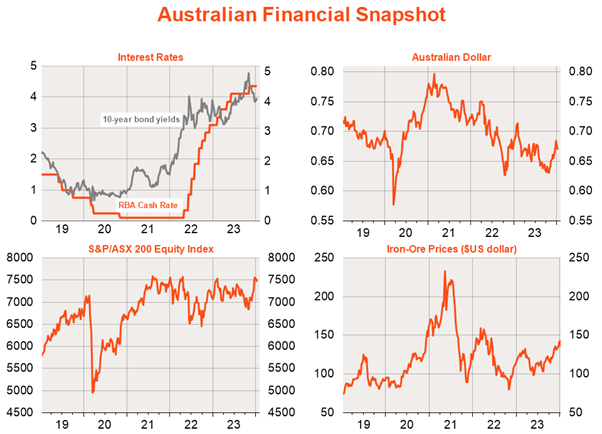

In financial markets, bond yields have stopped rising and equity markets are staging a recovery. The corporate earnings outlook is encouraging. The advent of new consumer-friendly artificial intelligence technologies is adding to investor excitement.

Source: LSEG Datastream, Betashares.

It’s almost too good to be true: can we truly achieve an economic ‘soft landing’?

We can dare to hope. In dealing with today’s high inflation, the history we feared may end up being a poor guide.

How does today compare with past inflationary environments?

Compared to the 1970s, the cyclically volatile manufacturing sector is today a smaller share of the economy, inflation expectations are better entrenched, and competitive pressures arguably stronger – thanks to widespread technology disruption and globalised markets.

The nature of the inflation shocks also differ. During the 1970s, the onset and return of high inflation was caused principally by two sharp oil price rises due to OPEC oil restrictions in both 1973 and 1979. These negative supply shocks not only pushed up inflation but also sharply reduced household income and corporate profits – making it harder to avoid recession. The post-COVID inflation burst, by contrast, was largely due to a stronger increase in demand relative to supply. Inflation lifted, but demand remained strong.

The post-COVID inflation we’ve experienced now appears largely to have been a series of one-off price level adjustments to clear markets suffering from short-term excess demand. This was first evident in the goods market during lockdown, but spilled over into services and labour markets when economies reopened.

Higher interest rates and inflation have so far merely reduced this degree of excess demand, without unduly hurting actual economic activity. At the same time, supply capacity in both goods and labour markets has gradually recovered.

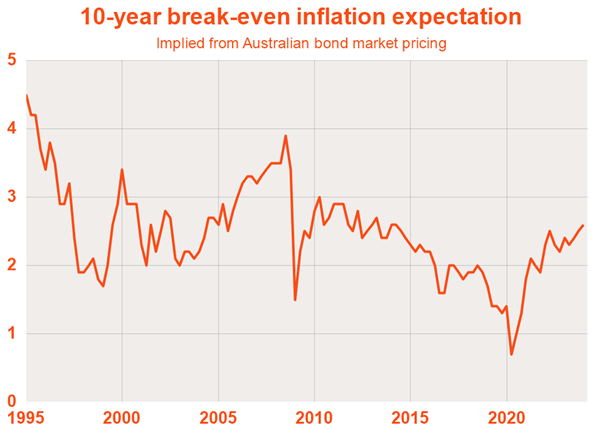

As would be expected, better-balanced markets are leading to a levelling off in pricing pressure. Importantly, with longer-term inflation expectations still contained, the much-feared entrenchment of high inflation through a self-defeating wage-spiral so far has not materialised.

Source: LSEG Datastream, Betashares.

Three risks that could make for a bumpy landing

While the economy appears to be improving, some risks remain. If the risks in one or more of these areas is realised, it could spell trouble for our ‘soft landing’ scenario.

Risk 1: Inflation and interest rates

Of course, risks remain. It’s still possible that the lagged impact of past interest rate increases catches up with the economy, especially as more households and businesses are forced to refinance cheap COVID loans at higher rates.

A modest slowing in growth could also still reach a tipping point, triggering a deeper downturn. But if inflation keeps trending down, either of these outcomes may only mean central banks cut rates more quickly and deeply, limiting the economic downturn.

Risk 2: Labour and unemployment

A more troublesome risk is if the declines in inflation start to slow, with wages and service sector inflation remaining too high given labour markets are still tight. Again, this risk should be averted provided overall economic growth keeps easing for a time, with a gradual lift in the unemployment rates in countries such as Australia and the US to around 4.5% – hopefully without triggering a deeper downturn.

If excess demand for labour slows or labour supply continues to recover, it’s possible that wages and services sector inflation slows further without a significant rise in unemployment.

Risk 3: Geopolitics

A final risk is geo-political – an escalation in the tragic conflicts in the Middle East and Europe that pushes up inflation through disruption of critical global food and energy supplies. Chinese tensions with Taiwan also persist, and the potential re-election of Donald Trump as US President later this year would be a new wild card.

So far at least, geo-political tensions remain contained, and the consequences of an escalation could be so disruptive that major players such as the US, Europe and the Middle East will likely continue to try hard to avoid it.

Global growth and markets

Against this backdrop, the most likely outcome for 2024 appears to be a further modest slowing in growth – but not recession – which allows for further declines in inflation and central bank interest rate cuts by year end. Lower rates would then allow a stabilisation in growth and moderate recovery as we head into 2025.

Such an outcome could be favourable to both bond and equity markets this year. High but falling bond yields bode well for decent income and capital returns from fixed-income markets. Lower bond yields could also support equity valuations at least holding around current levels, while allowing dividends and growth in earnings to deliver positive returns for investors.

In currency markets, easing global recession risks and likely deeper interest rate cuts from the US Federal Reserve (which raised rates more aggressively than most) would favour a weaker US dollar and firmer Australian dollar. A weaker US dollar, lower bond yields and improving global growth prospects later this year could also be positive for commodity markets, especially gold.

Within equity markets, an easing risk environment could also see the dominant outperformance of US large-cap technology stocks eventually give way to more investor interest in cheaper and long-neglected areas such as emerging markets, small caps, Europe, Japan and even Australia.

8 comments on this

Everthing in this article was wrong.

10 year goverment bond yields are going back up and so is inflation.

There is no way interest rates ca n be cut without creating more inflation.

Inflation is not under control in this country by a long shot.

I don’t know what world the author is living in, but it’s not the real world.

I agree with Jimmy, although cannot speak about bond yields. Did you base your argument with backed up data? If the top 1% possess half of the earths wealth, how real is your prediction if the data is skewed based on the predominant economic activity and possession of wealth from of the top 1%?

Everything in this article is correct taking in its context. Jimmy needs to look at the trend and not day to day movement. As far as George goes better I make no comment.

I thank David Bassenese for a general balanced opinion for the future.

Always a good read David, happy new year!

My favourite commentary is always a good read and assists me greatly with a view on where we heading with markets and the economy.

thank you.

Can I ask what evidence there is the current round of inflation was caused by “excess consumption” (eg is an increase in prices being misread as inflation) ?

In my mind inflation appears to have been initiated by business stress during covid periods coupled with supply cost increases for fuel (fuel costs effect everything in Australia due to transport distances). This was then further exacerbated by Philip Lowe’s inability to treat supply driven inflation differently to demand driven inflation at a time when residential mortgage rates make up less than 30% of all mortgages. Of course he also flogged the dead horse of raising interest rates to the point that we cant even be sure any reduction was due to raising rates – or just that with time those with savings that benefit from savings rate rises ran out of ideas on what to spend money on.

Of course too as interest rates rise, the banks reap a super windfall :- instead of receiving 1% of the value of all mortgages in profit on a 100% markup of the RBA interest rate (they probably never dropped to 100% of the lowest rate) – they receive 4.35% of the value of all mortgages on an RBA interest rate of 4.35%. Why should they receive a bigger commission on loaning RBA funds just because the RBA interest rate is raised ? It’s not like they actually worked for the windfall ?

Great article David. The inflation print came in favourably today in Australia which possibly further strengthens the argument for a soft landing.

Economist have consistently struggled to understand the markets and economy. I say this by being lucky to survive until 71 yo. With every major economic downturn, economists have been extremely slow in being able to model its onslaught. Well noted in the GFC and many other downturns in our economic history. Economists and Bankers constantly talk of inflation, often predicting a much worse scenario than that which we experience. We suffered the 80’s when our home loan was at 21%. Keating said it was the recession we had to have. My point is, just how well do our economic forecasters know and understand what is happening, just yesterday, our News financial advisors advised us that for unknown reasons inflation is falling faster than their anticipation. Being cynical, I think that our financial advisors and economic forecasters can begin to align themselves with our BOM Scientific staff who are constantly trying to model our weather and often fall short of the mark. Meanwhile, since shifting my SMSF to ETF’s I am over the moon at their returns. My strategy moving forward with my ETF’s is that when my modelling begins to experience a downturn, I will offload all and convert to our TF cash fund, hold until the slippery slide has shown signs of recovery, then buy back my ETF’s at a cheaper rate and move on. I used this same strategy with my Australian Super Investments a few years back and saved tens of thousands $ each time. I am only a mug investor, but it seems to work for me. Meanwhile, a short investment period of 2 years with UGC, saw my investments plummet over 60K while other mainstream superannuation returns were all in double figures. Go figure.