12 minutes reading time

The Future Made in Australia Policy

The ‘lucky country’…

The phrase “Australia, the lucky country” is frequently misunderstood. ‘The Lucky Country’ was the title of a book published in 1964 by noted academic Donald Horne. Far from being complimentary, Horne uses the term with irony, arguing that Australia’s abundance of natural resources has allowed us to enjoy success and prosperity without the need for innovation or excellence. The consequence is a society, economy and political system characterised by complacency and mediocracy, that undervalues education, science, and culture.

The Lucky Country – Donald Horne’s landmark commentary on Australian society

Source: Penguin Books Australia

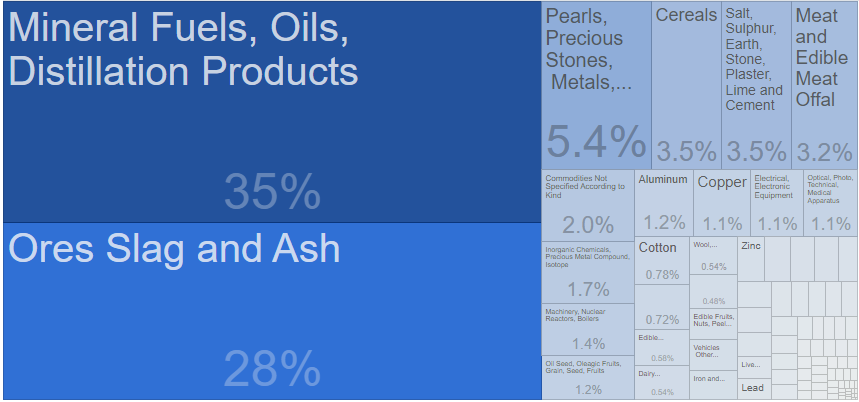

In 2023, Australia exported US$129.17 billion of coal, oil, and gas, representing 35% of total export volumes1. While we have come a long way since 1964, perhaps no better example of Australia’s complacency and political short-sightedness exists than in comparison with Norway. With similar levels of revenue from the export of natural resources, Norway created a sovereign wealth fund, the Government Pension Fund Global (GPPF), with assets now exceeding US$1.6 trillion2. In contrast Australia’s equivalent, the Future Fund, has less than US$150 billion3 in assets. Where Norway used tax revenues and royalties from oil and gas to create the GPPF, which plays a crucial role in Norway’s economy, funding public expenditures and ensuring financial stability for future generations, Australia has been criticised for its handling of coal, oil and gas revenues, often offering substantial subsidies to the industry, and not fully capitalising on potential royalties4, with the result we have little to show for decades of exploiting our natural wealth.

Australian exports by category

Source: Trading Economics

When the luck runs out…

As the world decarbonises, demand for Australian fossil fuels will decrease. The most recent International Energy Agency (IEA) Net Zero Emissions (NZE) roadmap shows that even with no change in climate ambition, demand for all fossil fuels will peak before 20305. For Australia, this is especially bad news. With substantially higher costs of production than countries like Qatar and the United States, and with China’s plans to develop massive oil and gas fields in the Caspian Basin and build pipelines into China and Southeast Asia6, it is entirely possible demand for Australia’s fossil fuel exports will decline far more rapidly than most commentators expect.

The consequences of declining fossil fuel export revenues for the Australian economy would be substantial. Declining national income impacts employment, wages, investment, and tax revenues. Pressure on the balance of payments can lead to currency depreciation and higher inflation. Effects would not be isolated to those industries directly affected. Declining tax revenues would impact public services such as healthcare, education. and social welfare. It would have flow-on effects for the entire economy. In short, lower living standards and potentially greater inequality. The decline of the coal industry in the UK in the 1960’s and 70’s is credited as the catalyst of a severe economic downturn for that economy.

A world in transition…

As the world transitions to net-zero emissions, the nature of the global economy will change. The new economy will be characterised by clean energy, storage solutions, low emissions vehicles, and new industrial processes. According to consulting firm McKinsey, electric vehicle battery cell production alone is forecast to increase more than 360% between 2020 and 20307.

According to Senior Research Scientist at the CSIRO Adam Best, the window to establish these industries of the future is short, and the rest of the world is moving faster than Australia8. In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act is fast tracking the development of clean tech industries and these policies are being mirrored in Europe, South Korea, India and of course China9.

A future made in Australia

The Future Made in Australia policy, announced in a speech made by the Prime Minister to the Queensland Media Club in April 2024, is Australia’s response to the Inflation Reduction Act and the rapidly changing global economy.

“We have unlimited potential. But we do not have unlimited time. If we don’t seize this moment, it will pass.”

- Hon. Anthony Albanese MP, Prime Minister of Australia

The Future Made in Australia policy is a series of measures aimed at “securing Australia’s place in a changing economic and strategic landscape”10. In the May 2024 Federal Budget, specific measures totalling AU$19 billion were announced targeting a range of clean technologies:11

- green hydrogen

- critical minerals processing

- green metals

- low carbon liquid fuels

- clean energy manufacturing, including battery and solar panel supply chains.

In addition, Export Finance Australia’s Nation Interest Account was expanded to allow support for projects critical to our national security or to strengthen resilience.

Picking winners and forever subsidies

Criticism of the Future Made in Australia focuses on the apparent willingness of the government to ‘pick winners’. In the view of most economists, government direct intervention leads to a misallocation of resources, a waste of taxpayer money and a distortion of market signals. There is no shortage of examples; the British and French governments wasted billions in today’s dollars supporting Concorde in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Similarly, the grants and loans by the British government to DeLorean to build sports cars in Northern Ireland in the 1970’s cost hundreds of millions of pounds. European subsidies for biofuel production in the early 2000’s not only cost billions but contributed to increases in food prices and severe environmental impacts12. Perhaps most relevant is the US government’s US$500 million plus in loan guarantees to solar panel manufacturer Solyndra in 2009. Solyndra subsequently filed for bankruptcy in 2011.

DMC DeLorean sports car. After receiving millions in government support, DMC filed for bankruptcy in 1982.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the face of this track record, it is hard to argue that the government’s announcement of AU$1 billion in support for solar panel manufacturing is not, in economist Nicki Hutley’s words, ‘a profligate waste of taxpayers’ money’13.

Further, it is arguable that private business could and would adapt to changing times and opportunities without direct government intervention, if they were presented with clear price signals and stable regulatory frameworks.

Unfortunately, we do not have a level playing field, and what some mainstream economists fail to grasp when they talk of ‘forever subsidies’14, is that relying on areas where Australia has existing competitive advantages (i.e. digging things out of the ground and shipping it overseas) no longer represents a viable future in a rapidly transitioning world. We must create new areas of competitive advantage, or face falling living standards.

Government intervention in markets does not always fail, there have been success stories. The growth of the car industry in Japan post World War II was in large part due to the partnership between the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and the automotive industry. Similarly, South Korea was able to build competitive advantage in shipbuilding and electronics with targeted subsidies, and financial incentives.

To have a realistic chance of success, efforts to re-industrialise Australia, and to build competitive advantages in the transition economy, should exploit our natural advantages, namely access to raw materials and a virtually unlimited supply of clean energy. Refining and processing critical minerals and transition metals should be a focus. Moving down the value chain in battery chemicals such as lithium and rare earths could substantially increase export revenue. However, we must also recognise our disadvantages which include a labour force that is relatively expensive and a skills shortage resulting from decades of underinvestment in vocational education and training15.

Other areas are less certain. The production of green steel and aluminium are areas that should play to Australia’s natural advantages. However, there are challenges. Green steel is made in an electric arc furnace (EAF) from direct reduction iron (DRI) made with green hydrogen (GH2) and using renewable energy. However, the hematite iron ore from Australia’s major iron ore producing region, the Pilbara, falls below the grade required for DRI using current technologies16. Research needs to be accelerated into technology combinations that allow the use of Pilbara hematite in DRI-based iron and steelmaking. NSW-based green tech company Calix has a pilot project producing zero-emission DRI in Bacchus Marsh, Victoria17. However, the 75-92% purity of the hot briquetted iron (HBI) produced is too low for green steel production, which currently requires around 95% purity. In February this year Rio Tinto, BHP and BlueScope announced a framework agreement to develop Australia’s first EAF DRI pilot plant18. Similarly Fortesque has committed to the development of a green iron production facility at Christmas Creek in Western Australia19.

Tianqi lithium hydroxide plant Kwinana Western Australia

Source: The Sydney Morning Herald

Aluminium is sometimes referred to as ‘congealed electricity’. The traditional Hall-Héroult smelting process consumes a significant amount of electricity. The electrolytic cells used to smelt aluminium need to be run 24 hours a day. Any shutdown longer than four hours requires a rebuild of the cell, which costs hundreds of thousands of dollars and takes several months. Hence it is critical for operations that the electricity supplied to the smelter is continuous, reliable, and of course cheap. There are currently four aluminium smelters in Australia, the largest being the Tomago smelter in the Hunter Valley, NSW. In February 2024, Tomago announced the appointment of Energetics in partnering to transition the smelter to firmed renewable energy, having rejected nuclear energy as too expensive20.

Tomago Aluminium Smelter NSW

Source: Tomago Aluminium

In 2023 Australia’s second largest smelter, the Rio Tinto majority owned Boyne Island smelter in Gladstone Queensland, announced the first gigawatt (GW) power purchasing agreement (PPA) in Australian history, agreeing to take all the electricity from the 1.1GW Upper Calliope Solar Farm, developed by European Energy Australia, for 25 years. Subsequenlty, Rio announced an offtake agreement for 80% of the output of the 1.4GW Bungapan wind energy project being developed by Windlab, a company majority owned by mining billionaire Andrew Forrest.

Other announcements in the Future Made in Australia policy seem more questionable. The role of green hydrogen in the energy transition is controversial with many commentators describing it as a ‘fig leaf for the fossil fuel industry’21. Due to its lack of energy efficiency and low volumetric energy density, green hydrogen is a poor decarbonisation solution for transport, electricity generation, heating, storage, and any industrial process capable of electrification22. Given just six hydrogen fuel cell vehicles were sold in Australia in 2023, plans to build a ‘hydrogen highway’ on the Australian east coast seems a poor use of taxpayer dollars.

While some green hydrogen will be required for green DRI, it will be nowhere near the 3.5 million tonnes over ten years implied in the May Federal Budget allowance of AU$6.7 billion. Legitimate emission reduction uses for green hydrogen, such as replacing grey hydrogen in the manufacture of ammonia for agricultural fertilisers and explosives, face challenges due to the high cost of green hydrogen relative to grey hydrogen, which is manufactured from natural gas and has high emissions. According to Australia’s largest fertiliser manufacturer, Incitec Pivot, green hydrogen as a feedstock “is not expected to be price competitive with natural gas for ammonia… until around 2040”23. In the absence of an explicit tax on carbon emissions, even with a proposed $2 per kilogram production tax credit, green hydrogen is not a financially viable alternative to grey hydrogen for large scale applications.

Fortesque’s PEM50 Green Hydrogen Plant in Gladstone

Source: Fortesque

Lastly, the wisdom of committing AU$1 billion in public money to support the assembly of solar panels24 and AU$0.5 billion to subsidise battery cell production25 is questionable. While Australia currently produces much of the raw materials used in both products, the actual components are dominated by China and both industries are heavily subsidised by both the US and Chinese governments.

“We will never outsubsidise the Chinese government….”

- Tony Wood, Energy Program Director, Gratton Institute

Conclusion

Australia’s path forward, in light of dwindling fossil fuel demand, lies in proactive and strategic innovation. The Future Made in Australia policy aims to derisk an economic shift to green technologies. While government intervention faces criticism, strategic investments have historically driven significant industrial advancements in other countries.

Australia should become a global leader in the production of lithium hydroxide and other battery chemicals, moving up the value chain and increasing the value of exports. So too are there opportunities in the production of green materials like steel and aluminium, noting that overcoming technical hurdles, such as adapting Pilbara hematite for green steel, is crucial. However, large grants for green hydrogen production and the final assembly of battery cells and solar panels are more questionable uses of taxpayer money.

Ultimately our success depends on evolving beyond natural resource exports, leveraging renewable energy, and fostering new industries. With decisive action and strategic foresight, Australia can secure economic stability and improve living standards, ensuring its continued prosperity in a transitioning world.

Future results are inherently uncertain. The information above may include opinions, views, estimates, projections, assumptions and other forward-looking statements which are, by their very nature, subject to various risks and uncertainties. Actual events or results may differ materially, positively or negatively, from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are based on certain assumptions which may not be correct. You should therefore not place undue reliance on such statements. Betashares does not undertake any obligation to update forward-looking statements to reflect events or circumstances after the date such statements are made or to reflect the occurrence of unanticipated events.

Sources:

1.https://tradingeconomics.com/australia/exports-by-category ↑

2. https://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/sovereign-wealth-fund ↑

3. https://www.futurefund.gov.au/-/media/F392074E5C624A19A0ACA3809B6AE366.ashx ↑

4. https://australiainstitute.org.au/post/australian-fossil-fuel-subsidies-hit-10-3-billion-in-2020-21/ ↑

5. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach ↑

6. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative, https://chinapower.csis.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative/ ↑

7. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/unlocking-growth-in-battery-cell-manufacturing-for-electric-vehicles ↑

8. https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2023-05-23/how-batteries-are-made-in-australia-mining-to-manufacturing/102356832 ↑

9. https://www.betashares.com.au/insights/america-awakens-the-stakes-couldnt-be-higher/ ↑

10. https://budget.gov.au/content/factsheets/download/factsheet-fmia.pdf ↑

11. https://budget.gov.au/content/overview/download/budget-overview-final.pdf ↑

12. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306261909001688 ↑

13. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/nicki-hutley-b6411812_jim-chalmers-rips-up-paul-keatings-economic-activity-7195985835408646145-fv2O?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop ↑

14. https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/made-in-australia-plan-risks-forever-subsidies-20240411-p5fiy7 ↑

15. https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-10/The%20Clean%20Energy%20Generation_0.pdf ↑

16. https://ieefa.org/articles/australia-must-act-quickly-overseas-competition-green-iron-grows#:~:text=IEEFA’s%20report%20highlights%20the%20fact,to%20low%2Dcarbon%20steel%20production. ↑

17. https://www.hydrogeninsight.com/innovation/australian-firm-says-it-can-slash-the-cost-of-green-hydrogen-based-iron-for-steelmaking-but-do-its-claims-stack-up-/2-1-1598049 ↑

18. https://www.bhp.com/news/media-centre/releases/2024/02/australias-leading-iron-ore-producers-partner-with-bluescope-on-steel-decarbonisation ↑

19. https://fortescue.com/what-we-do/our-projects/christmas-creek-green-iron-pilot ↑

20. https://reneweconomy.com.au/australias-biggest-smelter-to-launch-massive-wind-and-solar-tender-says-nuclear-too-costly/ ↑

21. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-12/federal-government-green-hydrogen-plans-labelled-greenwashing/101052282 ↑

22. https://www.betashares.com.au/insights/hopium-the-siren-song-of-green-hydrogen/ ↑

23. https://www.hydrogeninsight.com/industrial/we-will-make-green-ammonia-but-it-will-be-too-expensive-for-us-to-use-for-fertiliser-production-chemicals-firm/2-1-1559448 ↑

24. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-03-28/anthony-albanese-announces-solar-sunshot-manufacturing-program/103639924 ↑

25. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-23/national-battery-strategy-released-shore-up-supply-chain/103880892 ↑