7 minutes reading time

What we refer to as ‘ethical investing’ combines exclusionary or negative screening with norms-based screening, i.e. the exclusion of companies because of what they do, or how they behave. This particular approach to responsible investing has recently been the target of criticism largely around its perceived lack of real-world impacts.

The argument against ‘exclusionary based’ ethical investing has two main dimensions:

- Divesting from a company has little impact on the company.

- Owning a company and engaging with that company has more influence over its behaviour than divesting from it.

Much of this criticism originates with large institutional asset owners and fund managers.

The first of these arguments is somewhat of a straw man. It argues that the purpose of divesting is to raise the cost of capital of a company (how much it costs a company to issue shares or borrow in capital markets) and that divesting does not substantially impact the cost of capital.

A good example of this argument can be found in an article published in the Harvard Business Review in 2022 titled, “How Fossil Fuel Divestment Falls Short”1.The argument runs that the goal of divestment is “to create constraints on available capital in the fossil fuel sector, which should impede company operations in the target sector and limit shareholder returns, making the category less attractive to investors”. It argues that divestment doesn’t work because a sale on a secondary market, like a stock exchange, involves a seller and a buyer, and the new buyer has “a salient interest in making that asset perform….”.

This argument is somewhat of a ‘straw man’ and relies on ethical investors having a sole objective of changing the world. The reality is individuals who invest in ethical investment products have multiple objectives. While undoubtably they want to see their investments contribute to a more sustainable world, one of the primary motivations is to simply not profit from activities that have damaging impacts on the environment or society.

Further, the statement that fossil fuel divestment does not work is certainly true if done by a relatively small number of investors on a limited scale. However, that does not mean divestment campaigns cannot have real world impacts.

The divestment campaign against South Africa in the 1980’s is generally credited with hastening the end of the apartheid regime2. That campaign had two characteristics which impacted its success:

- It was near universal.

- It involved secondary boycotts. Not only did investors divest South African businesses, but they also boycotted the services of businesses that did do business with South Africa.

It is an interesting thought experiment to hypothesise the impact if every signatory to the UN Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI) or member of the Net-Zero Asset Managers Initiative (NZAMI) not only divested from fossil fuels, but also boycotted the banking, custody, broking, and insurance services of financial institutions that continued to lend to or insure new fossil fuel projects.

The second argument against divestment based ethical investing is that ownership of a company allows engagement that can help bring about changes in corporate behaviour. That investors can engage with management or the board of directors to change undesirable traits. If that fails, they can use their proxies to vote out existing directors and vote in new directors who will change corporate behaviour. The trouble here is that the argument is somewhat naïve. It makes assumptions about the simplicity of changing corporate behaviour without giving due regard to the fiduciary duty of company directors to all their shareholders, existing regulatory and legislative frameworks, and the impact of remuneration structures and incentive schemes aligned to revenue growth and commercial success, not sustainability outcomes in isolation.

Supping with the devil

There are few examples the critics of divestment can point to where engagement has resulted in the achievement of superior outcomes. One was the success of asset owners and managers, led by activist hedge fund Engine No 1., in electing three directors to the board of ExxonMobil in 2021, with the goal of pushing the energy giant to reduce its carbon footprint. However, in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and increases in the price of oil and gas, and despite the appointment of its new directors, Exxon has announced capital expenditure plans for 2023/24 of US$24 billion, an increase of 9% on the previous year3. This calls into question the effectiveness of the action by Engine No. 1 in achieving real world outcomes.

“Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, Engine No. 1 may have created a deadly distraction in our global fight against climate change, a fight that should be taken on by governments all over the world, not hedge fund activists. The only apparent positive result of this activism, at least from the perspective of Engine No. 1, is that the entity got a huge marketing boost in its efforts to raise funds.”

– Bernard S Sharfman, The Illusion of Success: A Critique of Engine No.1’s Proxy Fight at ExxonMobil4

In its Voting Matters 2022 report, NGO ShareAction found, “Asset managers across the board are hesitant to back action-oriented resolutions, which would have the most transformative impact on environmental and social issues5.”

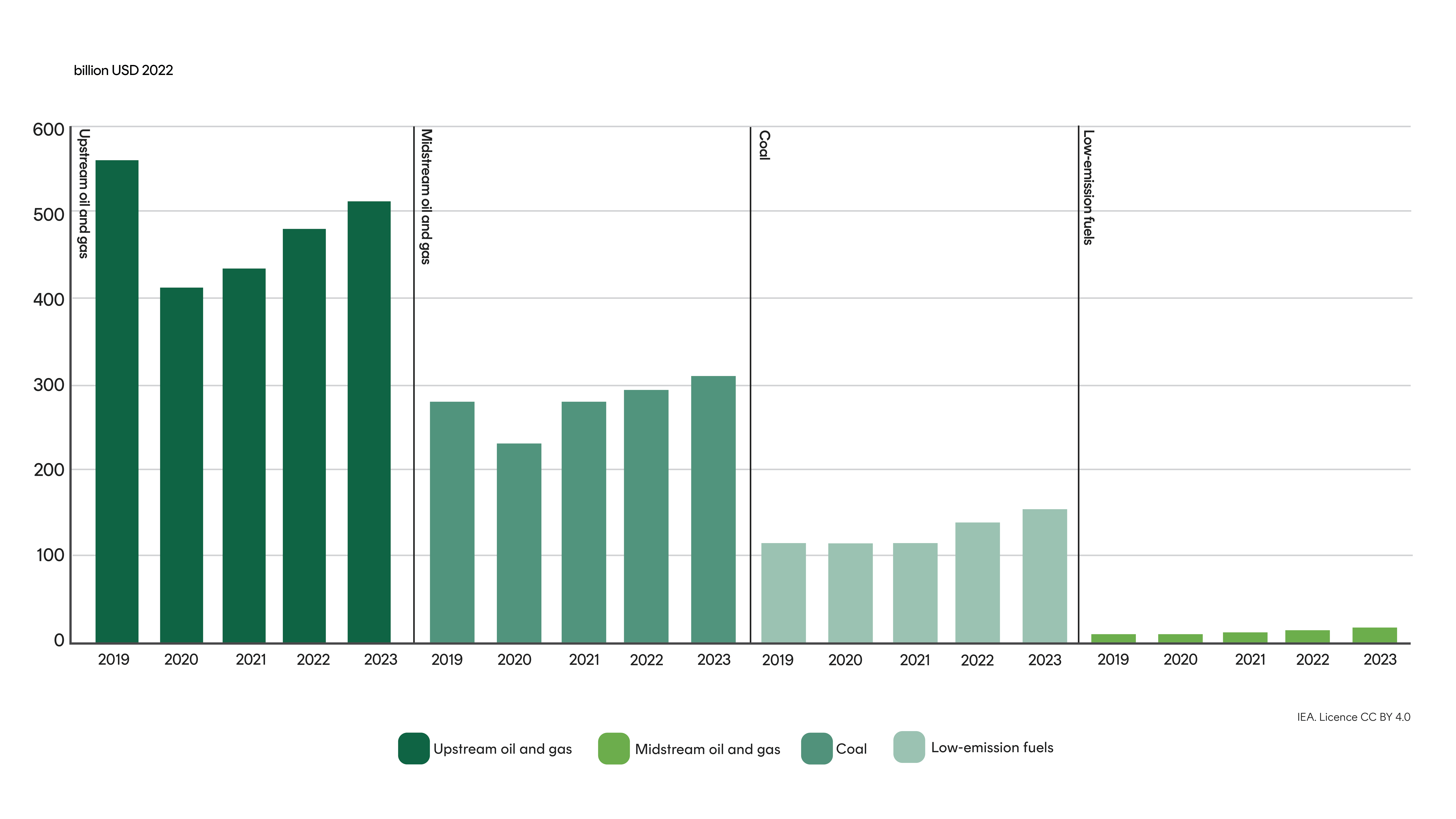

The question arises, if the UN PRI has more than 3,800 members and represents over US$121 trillion in AUM6, and Climate Action 100+ represents 700 global investors with US$68 trillion in AUM, and both organisations are committed to sustainability objectives and a transition to net-zero consistent with the objectives of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, why does the IEA forecast investment in coal, oil and gas to exceed US$1 trillion in 20237?

Fuel Supply Investment, 2019-2023

Source: IEA World Energy Investment 2023

The lack of effectiveness of engagement with fossil fuel companies in leading to the adoption of transition plans consistent with the Paris Agreement has led the Church Commissioners for England, which manages the Church of England’s £10.3bn endowment fund, to divest from all oil and gas majors from its portfolio in June this year8. Clearly, engagement has its limitations.

Investors who are concerned with sustainability outcomes should rightly be suspicious of the claims of managers that their stewardship programs lead to real world outcomes. In 2019 the UN PRI published Active Ownership 2.0, a response to concerns that asset manager stewardship activities had become overly concerned with the process of engagement and not the outcomes. That it was more about marketing and brand differentiation than real world impacts.

Conclusion

The critics of ethical investment argue that approaches focused on the exclusion of companies pass up the opportunity to influence those companies through engagement and proxy voting. However, it has been the experience of Betashares that exclusion is not a barrier to engagement, and in fact excluded companies frequently wish to engage to understand what actions they need to take to end that exclusion. Most successful engagements occur when the sustainability objectives of the investor do not conflict with the commercial self-interest of the company.

Climate change is the most serious threat facing our economy and society. To quote UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, “Climate change is here. It is terrifying”9. The IEA has made it clear that to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius there can be no further expansion of fossil fuel production10. Ethical investors, like the Church Commissioners for England, understand that engagement with fossil fuel companies will not lead to an end to fossil fuel expansionary capital expenditure. Only substantive change in global climate policy and increased ambition from political leaders will achieve that outcome. Turkeys do not vote for Christmas.

Ethical investors can at least sleep well knowing their investments have not contributed to a worsening climate outcome, and they have not engaged in actions that distract from the need for substantive policy change.

1. https://hbr.org/2022/11/how-fossil-fuel-divestment-falls-short#:~:text=There’s%20one%20major%20problem%20with,the%20opposite%20of%20what’s%20intended

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disinvestment_from_South_Africa

3. Source: S&P Global Insights, ExxonMobil releases 2023 capex of $24 billion, up 9%; keeps production flat

4. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3898607

5. https://shareaction.org/reports/voting-matters-2022/introduction

6. https://www.unpri.org/annual-report-2021/how-we-work/building-our-effectiveness/enhance-our-global-footprint

7. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/54a781e5-05ab-4d43-bb7f-752c27495680/WorldEnergyInvestment2023.pdf

8. https://www.churchofengland.org/media-and-news/press-releases/church-commissioners-england-exclude-oil-and-gas-companies-over

9. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2023-07-27/secretary-generals-opening-remarks-press-conference-climate

10.https://www.iea.org/news/the-path-to-limiting-global-warming-to-1-5-c-has-narrowed-but-clean-energy-growth-is-keeping-it-open

3 comments on this

Great article

Really interesting write-up, Greg. I question how effective ESG investing (in its current form) can be without screens that are defined relative to peers within a company’s industry.

For instance, how flexible is Betashares with the application of its exposure limits for ESG portfolios? Specifically, can a company operating in an excluded industry (with a limit of 0% of revenue) ever make it past the screen? For example, if an oil company has a significantly lower carbon footprint compared to its peers (but still towering above other industries) and was leading research and investment on sustainable technologies, would it still be screened out?

I ask this because I think my biggest concern isn’t whether we should be applying ESG screens but how such ESG screening criteria are defined. To me, an oil company that is reducing its carbon footprint by 3% every year is making a bigger difference than a large bank cutting 10% off of a minuscule footprint. Logically, companies that operate in environmentally damaging industries offer the biggest opportunity to make a positive impact. For example, this 2023 NBER article found that US fossil fuel firms were leading the charge on green innovation and green patents: https://www.nber.org/papers/w27990. It makes a lot of sense too – if you wanted to reduce crime, you wouldn’t be giving more funding to areas with low crime but targeting high-risk populations (e.g. delinquent youth, unemployed people near organised crime etc.)

This supports the claim made in this article that diverting capital to companies with good environmental ratings often didn’t amplify that impact: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4359282

Really good article thanks, Greg. It should be required reading across the funds management sector!