8 minutes reading time

This information is for wholesale client use only.

A little while ago, the Financial Times newspaper highlighted the curious case of an ESG-labelled bond fund run by an esteemed global fund manager, pointing to some of its “eyebrow-raising” bond holdings1. These included Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest oil producer, as well as Saudi Arabia itself, a country not exactly known for an exemplary human rights record nor particularly likely to trouble the Nordics or NZ at the top of the global good citizen tables!

Similarly, an equally well-regarded global manager was pinged in the article for including companies like Marathon Petroleum (a crude oil refiner), Schlumberger (oil services) and Kinder Morgan (oil and gas pipeline) in an equity ETF that claimed to exclude fossil fuel stocks.

Two questions immediately come to mind. How is something like this possible? And what can advisers do to avoid putting ethically-minded clients into funds like these?

Welcome to the world of responsible investing – also known as ethical investing, sustainable investing, or ESG investing (for ‘environmental, social and governance’).

The ethical investing landscape, November 2020

However you label it, responsible investing is on the rise. From a niche activity just a few years ago, responsible investing is becoming increasingly mainstream. Blackrock estimates that global assets invested in ESG ETFs will hit $400 billion within a decade2. We ourselves have seen tremendous take-up in our ethical ETF range since we launched the first of our ethical ETFs in 2017, with more than $1.8 billion in funds under management currently, invested by tens of thousands of investors3.

Two broad trends appear to be driving this growth:

- an increasing desire among investors to invest in line with their values, in a way that promotes socially desirable outcomes, and

- an increasing realisation that companies with elevated ESG risk profiles are at risk of underperformance.

The demand for ESG exposures has been coming from a wide range of sources – younger investors, to be sure, but also family offices, charitable foundations and even super funds looking to offer sustainable investing options to their members. Not surprisingly, product issuers have responded with a raft of new products aiming to capitalise on the trend, both in Australia and overseas.

And herein lies one part of the answer to the question of how a Saudi Arabian oil company can find its way into an ESG fund: managers are rushing to capitalise on the surging popularity of ESG investing and may be tempted to cut corners or simply not explain adequately the methodology behind their investment processes. ‘Greenwashing’ – the practice of slapping an eco-friendly label on a conventional fund to burnish its environmental credentials – is unfortunately a growing problem.

Less cynically, ethical investing is still relatively new, and it’s growing and changing fast. That means there are not yet broadly-accepted standards for what constitutes ethical investing.

For example, a manager may take the view that Marathon Petroleum should be included in an ESG offering because it is ‘less bad’ than other oil companies based on one or other ESG metric. This is arguably a defendable view, if the thinking is disclosed properly, but one we suspect does not resonate with most retail investors.

Add to this the complication that ESG data from third-party providers tends to be patchy or inconsistent – leading to some perverse results – and you have a recipe for confusion.

The good news is that, in a world of increasing transparency and access to information, it’s becoming harder for product providers to get away with dubiously-labelled ESG offerings. Investors are more educated than ever, with increasingly useful and relevant resources at their disposal. Want to check how Apple’s supply chain is regarded? Go to the Ethical Consumer Guide. Interested to learn which banks are the biggest lenders to fossil fuel projects globally? Check out BankTrack. Plus, at least with ethical ETFs, full holdings are available daily. There’s nowhere to hide.

Five guidelines

Returning to the second question we posed up front: what can advisers do to avoid putting ethically-minded clients into funds that don’t meet their expectations? Or, to put it more positively, how can advisers ensure they are serving these clients with products that best meet their expectations?

Here are a few guidelines:

1. Go beyond the label.

Just because a fund has ‘ESG’, ‘Ethical’ or ‘Sustainable’ in its name doesn’t mean it will do what you think it will do. It quite possibly will not. Dig a bit deeper.

2. Be clear on what’s important to your client and confirm the fund matches their expectations.

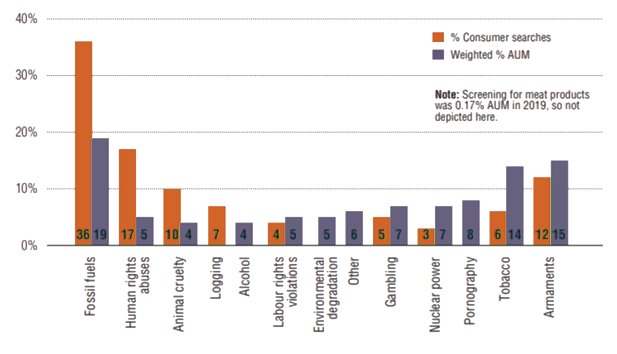

A recent industry report by the Responsible Investment Association Australasia (RIAA) noted that the exclusions applied by investment managers are frequently not aligned to what’s important to ethically-minded investors4. For example, among the most common activities screened out by investment managers are controversial weapons, alcohol and tobacco, yet consumers are often more interested in fossil fuels, human rights and animal cruelty. So it’s good practice to check: does the fund under consideration have zero tolerance for the activities that really matter to your clients? Emerging issues that have become important for ethical investors are often not well covered by traditional ESG data providers (e.g. gender diversity on boards, junk foods, animal cruelty including live animal exports).

The figure below highlights the variation between exclusions respondents in the RIAA survey applied and the most important exclusionary screens according to consumers (based on data from RIAA’s Responsible Returns online tool, which shows the key issues customers search for when choosing a responsible investment product).

Negative screening – % of consumer searches on Responsible Returns vs survey respondent exclusions (weighted by % AUM)

Source: RIAA, Responsible Investment Benchmark Report, 2020 Australia

3. Understand the methodology.

This is important and, at least in the case of an ETF, it’s not hard to find out. Access the fund’s web page and you should be able to review the investment rules used by the fund. For the greatest level of detail, access the index methodology document for the index the ETF aims to track – that will spell out exactly which activities are excluded, and what tolerances or thresholds are applied in making the assessment. For example, refer to the index methodology document for the index the B ETHI Global Sustainability Leaders ETF aims to track.

4. Review the fund’s holdings (or suggest your client review them).

For an ETF, the full portfolio will be available on the ETF issuer’s website each day. This will reduce the chance of any nasty surprises once your client has invested.

One other point to note.

Investors are increasingly interested to understand how a fund votes its shares when ESG-related resolutions come up at annual meetings. After all, proxy voting is an important way in which investors can have an impact on corporate behaviour, and ethical investors have a right to expect their investment managers will vote in a way that advances the values embodied in the fund. So we add a fifth guideline.

5. Check whether the fund votes its shares in a way that aligns with the values of the fund.

Information about the fund’s proxy voting record should be accessible on the issuer’s website. If shareholders at Starbucks’ annual meeting considered a proposal for enhanced carbon emissions disclosure, or gender pay gap reporting, how did the fund vote and why? For example, here is the Betashares ESG-related Proxy Voting Report for the 2019/2020 financial year.

Conclusion

For advisers new to the ethical space there is no doubt some complexity here. But for those willing to make the effort to understand these issues, the rewards will be more substantive conversations and a deeper connection with the growing pool of investors who increasingly see the issues of sustainability and ethics as core to the way they approach the investment process.

For their part, it is also fair to say that if product issuers want to earn the trust of investors, they need to be absolutely transparent about how their products work. That means easily accessible information on their investment process, clear explanations of how exclusionary screens work, full portfolio holdings disclosure and transparent proxy voting records.

We have written about this quite extensively in the past but I’d be remiss not to comment that, in a broad sense, it is our observation that passive product issuers in the ethical/ESG space in Australia have tended to be ‘light green’ in their screening approach, letting through too many companies with dubious ethical credentials, so that they have limited appeal to retail ethical investors. Active managers by contrast can be more rigorous in their ethical approach, but they tend to be very expensive and add additional risk through active stock-picking and lack of diversification.

BetaShares has attempted to take the best of both approaches and to construct funds with diverse portfolios and genuine ethical screens that investors can access at a fair price.

Investors in our ethical funds have also been rewarded with strong performance. Over the five years to 30 October 2020:

- The index the ETHI Global Sustainability Leaders ETF aims to track has returned 14.5% p.a., outperforming broad global shares by 6.0% p.a.

- The index the FAIR Australian Sustainability Leaders ETF aims to track has returned 10.3% p.a., outperforming broad Australian shares by 3.5% p.a.5

For more information on our ethical range of ETFs, click here.

Investing involves risk. The value of an investment and income distributions can go down as well as up. Before making an investment decision you should consider the relevant Product Disclosure Statement (available at www.betashares.com.au) and your particular circumstances, including your tolerance for risk, and obtain financial advice. An investment in any BetaShares Fund should only be considered as a component of a broader portfolio.

1. https://www.ft.com/content/ac10773a-a975-11e9-b6ee-3cdf3174eb89, as at 20 July 2019.

2. Cited in https://www.ft.com/content/ac10773a-a975-11e9-b6ee-3cdf3174eb89, as at 20 July 2019.

3. Source: BetaShares, as of 19 November 2020

4. Responsible Investment Association Australasia, 2020, Responsible Investment Benchmark Report, 2020 Australia

5. Source: BetaShares. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance of any index or ETF. You cannot invest directly in an index. Does not take into account ETF fees and costs. Broad global shares represented by MSCI World (Ex-Aus) Index (AUS). Broad Australian shares represented by S&P/ASX 200 Index.