5 minutes reading time

Investors have flocked to ETFs due to their liquidity, transparency and the ease of access to different markets and asset classes.

For investors considering entering the ETF market for the first time, it is important to understand the structure and how they are brought to market.

The ETF liquidity structure

ETFs are similar to managed funds, but are traded on market, so you buy and sell units in the fund just as you would individual stocks. However, unlike some other listed vehicles such as listed investment companies (LICs), ETFs typically trade around their fair value.

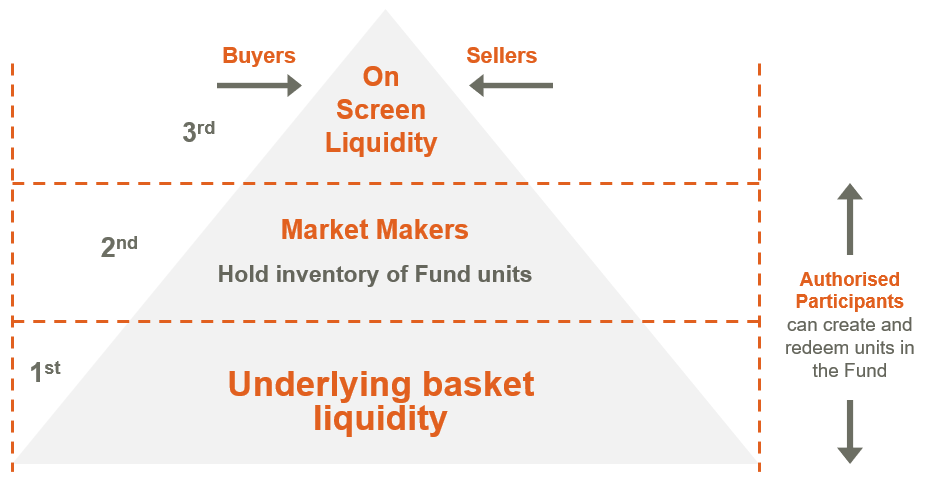

How this occurs is down to three layers of liquidity, as illustrated below, and covered in more detail here.

The important thing is that whilst ETFs can trade like stocks due to the ‘natural volume’ from investors buying from and selling to one another, there are extra layers of liquidity, which generally mean they are as liquid as their underlying exposure.

In addition to natural buyers and sellers, Market makers are liquidity providers who hold inventory of ETF units and provide volume on both the bid and the offer.

Authorised Participants (APs) are typically institutions that create and redeem units directly with the ETF provider, similarly to how investors access an unlisted fund.

The open-ended structure of an ETF means that the fund can grow and shrink in line with demand and is typically as liquid as its underlying exposure.

It is also this ‘open-ended’ mechanism that tends to keep an ETF trading near fair value. If an ETF’s trading price was to move away from its fair value, and for example the ETF was trading at a discount, APs could buy the undervalued ETF units and sell the underlying holdings at a higher price. This process should bring the ETF price back near its fair value. APs would enter the opposite transactions if the ETF was to trade above fair value.

In contrast, LICs have a ‘closed-ended’ structure. There is a fixed number of units, and so the forces of supply and demand can result in these types of funds trading at a premium or discount to their fair value.

What is the fair value of an ETF?

Just like a managed fund, an ETF has a Net Asset Value (NAV). This is the total value of the holdings of the fund, minus its liabilities. To calculate the fair value or NAV per unit, the fund’s net value is then divided by the number of units in the fund. For example, if a fund held $1,000,000 worth of equities and there were 100,000 units in the fund, the NAV per unit would be $10.

An independent administrator calculates the NAV as at the end of the day, based on the closing price of each of the underlying holdings once they have ceased trading, and the NAV is then checked by the ETF provider.

How do you know an ETF is trading at or near its fair value?

Unlike unlisted managed funds, you can trade an ETF on the exchange throughout the trading day. You will also notice that the unit price of an ETF will tend to move throughout the day. So how do you know it is trading at or close to its fair value?

During each trading day, an ETF’s price and the Market makers’ bid/offer prices will generally be based on an indicative net asset value (iNAV). The iNAV, like the NAV, is calculated based on the total value of all the fund’s underlying holdings, however a fund’s iNAV is updated at very frequent intervals based on live market prices during each trading day.

For an ETF holding Australian shares, this is straightforward because the underlying holdings are trading at the same time as the ETF.

Fair value for international exposures

ETFs are a simple, cost-effective way for investors to obtain exposure to international markets. But how do you calculate the fair value if the ETF trades in a different timezone from its underlying securities – for example, a U.S. equity ETF that trades on the ASX, such as the BetaShares NASDAQ 100 ETF (ASX: NDQ)?

In this case, as an iNAV may not be available for international exposures, a proxy can be used to determine the best estimate of fair value for the underlying securities that aren’t trading at the same time as the ETF. This is often done using futures, which trade around 23 hours a day.

For example, as NDQ is trading whilst the U.S. sharemarket is closed, the fund’s fair value may be estimated using NASDAQ-100 futures contracts, which continue to trade during Australian market hours, and give a good representation of movements of the NASDAQ-100 Index. It is typically futures which determine how a market will open compared to the previous day’s close as international investors take a view on that market. You will notice the Australian market typically does not open at exactly the same price as it closed yesterday – a lot of this difference is due to futures trading in international markets whilst we are asleep.

Summary

One of the key benefits of ETFs is that they typically trade around fair value based on their underlying exposure.

To assess whether an ETF’s market price is near its fair value, you can compare the iNAV (where available) of an ETF to the price at which you can buy or sell units in that ETF, or compare movements in futures contracts representative of the market to changes in the price of an ETF, if an iNAV is not available.

BetaShares Funds’ iNAVs are, where applicable, either displayed and updated regularly on our website, or in some cases, can be viewed on broker websites using an ASX code. For example, you can find the iNAV of the BetaShares Australia 200 ETF (ASX: A200) using the code YA20.