4 minutes reading time

With the Fed officially commencing its easing cycle with a 50-basis point cut, much of the debate now shifts to the softening US labour market and the degree of further easing that’s required.

However, it’s worth remembering that the Fed is quite late to the global easing cycle, with the Bank of Canada (BoC) already 75 basis points into its cutting cycle, after starting in June.

Canada is a particularly relevant proxy for Australia – both are small open economies, both have highly indebted household sectors and outsized residential property markets (as a share of GDP and national wealth), and both economies are tied to the global commodity cycle.

In addition, both economies have been highly reliant on population growth to drive GDP growth, with poor levels of productivity growth a feature for years.

The other reason to look at Canada is because the US is by far its largest trading partner. As a result, the lags from a slowing US economy showing up in Canadian data is much shorter and the impact magnified (i.e. the Canadian economy is highly “leveraged” to the US economy).

The adage goes “when the US economy sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold”, and this is especially true for Canada, and it may be a decent leading indicator for what might happen to the Australian economy over the next 6 months.

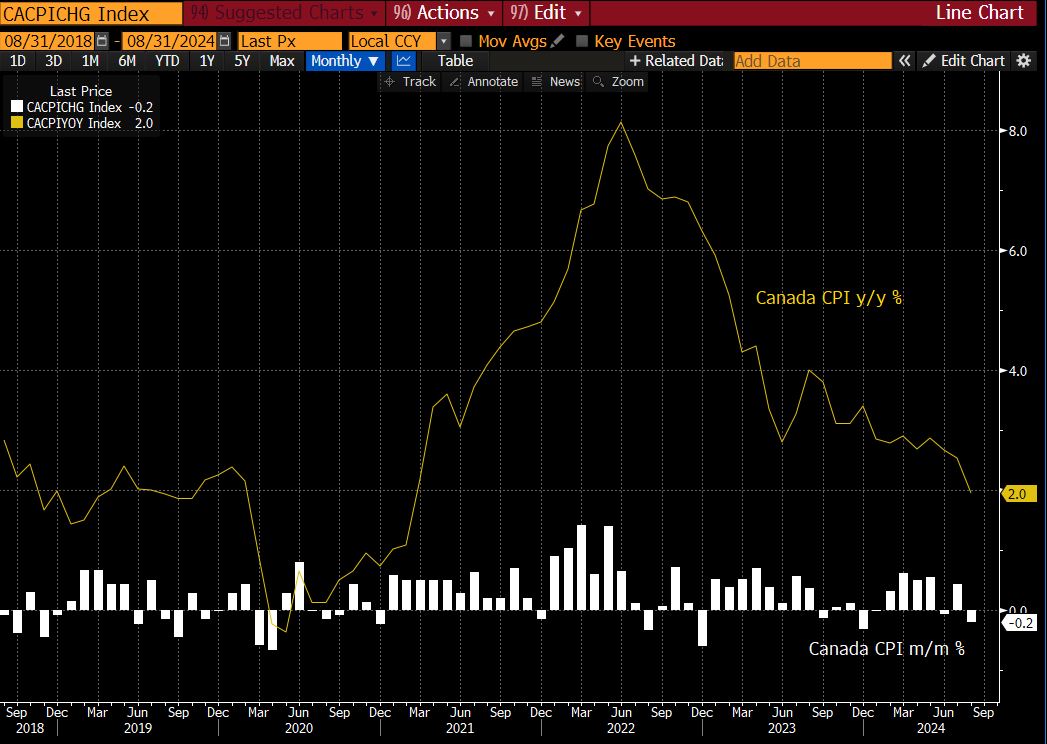

I bring up Canada now because not only is its central bank well into rate cuts, but also because Canadian CPI data recently entered deflation territory, with prices contracting over the month of August (-0.2% m/m vs 0.0% exp).

The incredibly soft inflation data has also come on the back of a very weak labour market, which has cooled far more aggressively than expected. After reaching a cycle low of 4.8% in mid-2022, the Canadian unemployment rate has steadily risen to 6.6% over the past 2 years.

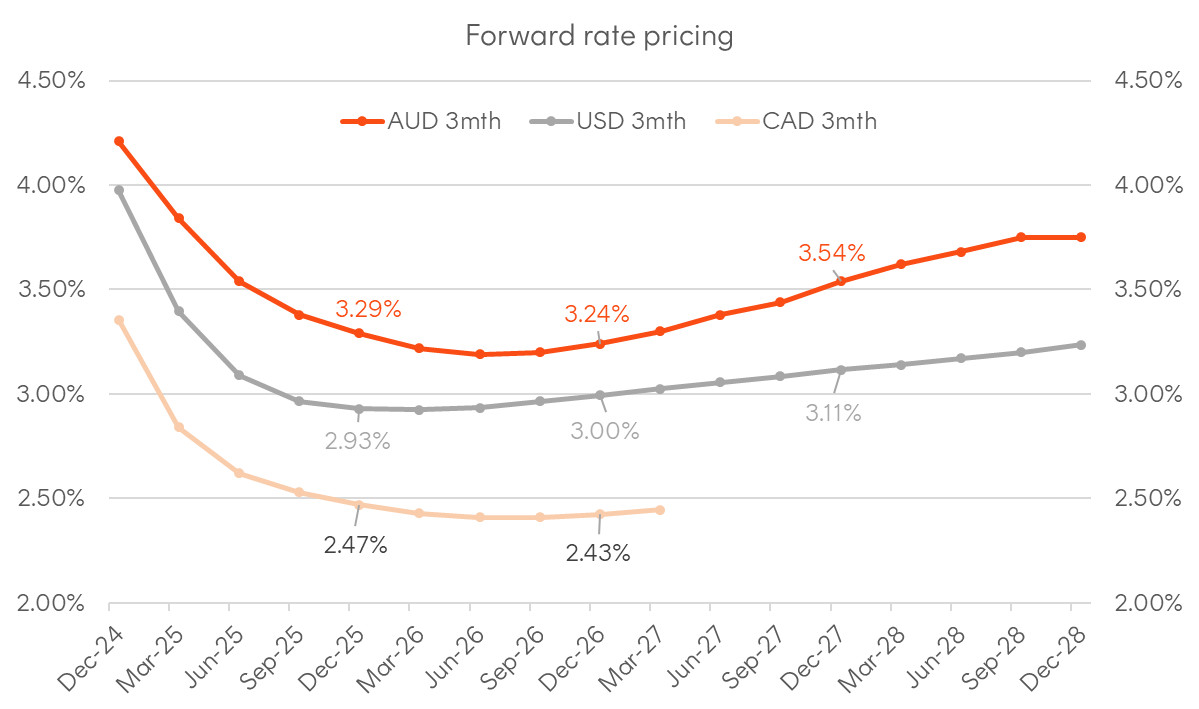

There’s a decent argument to be made that the BoC needs to be cutting much more aggressively than it currently is. The current BoC policy rate is 4.25%, almost the same as the RBA cash rate, but the Canadian 10-year government yield is 100 basis points below our 10-year benchmark.

It’s our view that Australia will be pulled into this global easing cycle – we’re too small and globally linked not to.

In addition, we’re particularly exposed to another economy that’s also dealing with deflation pressures, in China. Duration has a tailwind overall, based on the recent performance of fixed rate bonds, but allocators might be tempted to gravitate towards global bonds given the relative timing of rate cuts.

However, when taking a 12-month forward-looking view, there’s already a lot of rate cuts priced into global yield curves and arguably far more upside to Australian bonds. If the global forces of rapidly slowing inflation and a weakening labour market truly make their way here, this should result in a more aggressive repricing at the long end of the Australian yield curve and therefore outperformance.

Chart 1: Canadian inflation data

Sources: Bloomberg, Statistics Canada

Chart 2: Canadian unemployment rate

Sources: Bloomberg; Statistics Canada

Chart 3: Australian and Canadian interest rate

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 4: Forward 3-month interest rate pricing

Source: Bloomberg, as at 20 September 2024. Compared SOFR futures (USD), Bank Bill Futures (AUD), and CORRA futures (CAD).